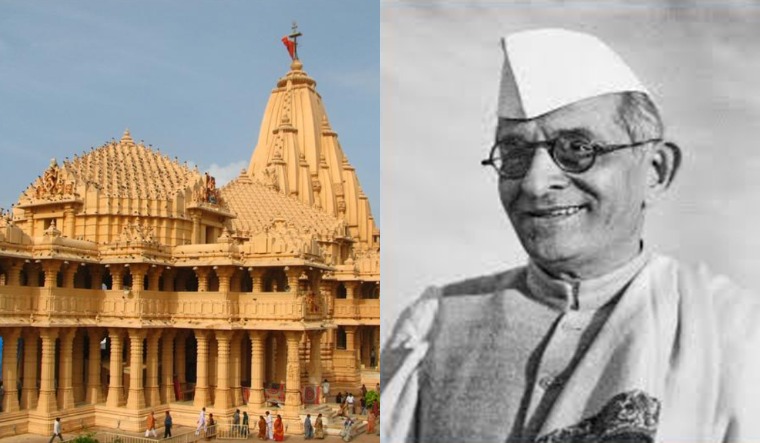

Fervour for the bhoomi pujan of the Ram mandir in Ayodhya is gathering steam steadily even as concerns over COVID-19 persist. The expected participation of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, via virtual means or in person, at the ceremony has already triggered debate. The debate also has some parallels in an earlier shrine-building initiative around 70 years: The reconstruction of the Somnath Temple in Veraval, Gujarat.

The Somnath Temple is revered for housing one of the 12 jyotirlingas—places where lord Shiva is believed to have appeared as a column of fire. But the history of the revered shrine has been associated with it being the target of Muslim invaders.

The most well-known attacks on the Somnath Temple are those by Mahmud of Ghazni in 1025-26, Allauddin Khilji in 1296 and Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in 1665. The first time the Somnath Temple was believed to be targeted by a Muslim invader was as early as 725AD, when the Arab governor of Sindh, Junayd ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Murri, destroyed it. However, historical evidence for this remains sketchy.

While it was rebuilt after each such invasion, the Somnath Temple was looted in between, without the shrine being destroyed. In 1783, the Holkar dynasty built a new shrine adjacent to the one destroyed by Aurangzeb.

Given this history, by the time of Independence, the saga of the Somnath Temple was a potent symbol of the aggression of Muslim invaders. Somnath was located in Junagadh, a small princely state ruled by a Muslim dynasty. When the nawab of Junagadh, Muhammad Mahabat Khanji III, decided to accede to Pakistan, despite the opposition of his predominantly Hindu subjects, the Indian Army annexed the state on November 9, 1497.

Just days later, then home minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel announced the decision to rebuild the Somnath Temple. Speaking at a public meeting at the site of the old temple on November 13 that year, Patel called on people of Saurashtra to do “their best” for the project. Patel had then called the reconstruction of the Somnath Temple a “holy task in which all should participate”. The Shivling idol of the rebuilt Somnath Temple was installed in the presence of Dr Rajendra Prasad, the first president of India, on May 11, 1951.

Much has been said and written about Sardar Patel’s role in leading the reconstruction of the Somnath Temple, most notably his determination despite then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru considering the project as a sign of “Hindu revivalism”. Sardar Patel’s commitment to the Somnath project has come into focus in recent years, with even Modi praising him. After inaugurating the Statue of Unity in November 2018, Modi had said if it were not for Patel, ‘Shiv bhakts’ would have needed visas to visit the Somnath Temple.

But Patel, who died in 1950, was not the only face in the Nehru government who backed the initiative to build the Somnath Temple.

Kanaiyalal Maneklal (K.M.) Munshi (1887-1971), a minister in the Jawaharlal Nehru government, chronicled the history of the Somnath Temple and the struggle to rebuild it in multiple books.

Munshi, a writer and educationalist, served as Union minister for food and agriculture from 1950 to 1952 in the Nehru government. He was chairman of the trust constituted to build the Somnath Temple with public funds and after the death of Patel, was, arguably, the government face of the project.

Munshi’s book Jaya Somnath (1937) has been seen by both supporters of the temple reconstruction effort and its opponents as having promoted the temple as a symbol of Hindu restoration.

Munshi had described the effort to build the Somnath Temple as a response to a “national urge”.

In his 1997 book Lives of Indian images, scholar Richard H. Davis argued the BJP had evoked Munshi’s successful pursuit of the Somnath Temple project in its Ram mandir agitation. “Like Munshi, they [BJP] claim that the restoration of a long-abandoned temple site is essential to the integrity of Hindu society, and have mobilised towards this end. Evoking Munshi’s successful project, the BJP has portrayed its mobilisation to build a Ram temple atop the site of the Babri Masjid as a continuation of the ‘Spirit of Somanatha’,” Davis wrote.

Standing up to Nehru

In a letter to Nehru, dated April 24, 1951, Munshi countered the prime minister’s description of the Somnath Temple project as “Hindu revivalism”.

“I have laboured in my humble way through literary and social work to shape or reintegrate some aspects of Hinduism, in the conviction that that alone will make India an advanced and vigorous nation under modern conditions…,” Munshi wrote.

“It is my faith in our past which has given me the strength to work in the present and to look forward to our future. I cannot value freedom if it deprives us of the Bhagavad Gita or uproots our millions from the faith with which they look upon our temples and thereby destroys the texture of our lives. I have been given the privilege of seeing my incessant dream of Somanath reconstruction come true. That makes me feel—makes me almost sure—that this shrine once restored to a place of importance in our life will give to our people a purer conception of religion and a more vivid consciousness of our strength, so vital in these days of freedom and its trials,” Munshi argued.

Munshi was the co-author of the book Somanatha—the Shrine Eternal, chronicling the history of the Somnath Temple. In its 1965 edition, the book noted the cost of construction of the temple was Rs 24,92,000.

Move to the right

Munshi left the Congress in 1959 to start the Akhand Hindustan Movement and later played a role in forming the centre-right Swatantra Party with C. Rajagopalachari. The Swatantra Party was a short-lived political party that batted for private enterprise at a time of socialism.

Munshi was a delegate at the conference in what was then Bombay in 1964 that led to the creation of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad. Munshi also founded the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan educational institution in 1938.