When Che Guevara made the last run for his life, he scrambled up a steep ravine in a rough gorge where the Andes become valleys, and straight into the command post of the Bolivian Army unit led by Colonel Gary Prado Salmón.

In that very moment, the tides of fate held the balance between revolutionary momentum and state power in a global clash of ideologies that played out in that remote Bolivian canyon. What happened next was Prado’s call.

His decisions and what followed kept him one of the central figures in a battle that sealed the fate of the continent for decades to come. Prado died this week at 84 in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, in the Bolivian east.

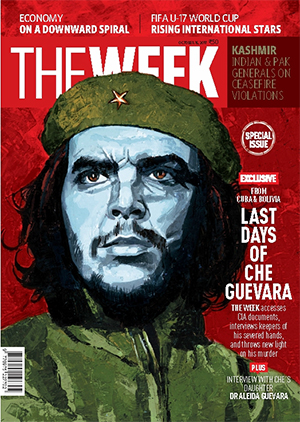

One of the most iconic figures of the Cold War, Che would die that next day in 1967. In the 55 years that followed Prado was hailed for capturing “one of the most wanted men in the world,” and vilified by others for the controversy around the CIA’s role and Guevara’s execution without a trial, both decisions made by others.

Prado received many accolades, was named a Bolivian national hero by the Bolivian Congress and was protected by the armed forces; he eventually became a general and a diplomat. But the political winds blow hot and cold, they blow hard and in complicated ways, and they were not gentle on Prado.

He became a target of leftist groups and some later political leaders saw him as a liability. His name remained a raw point at the hinge between the fluttering of the red banner of communism and those who fought against it.

At his death, the current Bolivian High Military Command under leftist president Luis Arce banned all military personnel from even standing as honour guards at his wake, an honour given to all military veterans.

Prado’s role in the defeat of Guevara’s guerilla forces marked the end of the first significant and most public attempt to spread Castro’s Cuban revolution in Latin America. His role in this pivotal moment cemented a legacy as a key figure in the struggle between left and right forces in the continent.

On October 8, 1967, the noontime sun bore down upon the rugged terrain at La Quebrada del Yuro in southeastern Bolivia. Che Guevara and his ragtag band or guerillas had been spotted by night before by a potato farmer. By daybreak, the Bolivian army held all high points along the hills rising from the canyon.

Ambushed and vastly outnumbered by troops against jagged rocks and steep inclines, Che and his meagre fighters were caught off guard and scattered, and Che himself was wounded early in the battle. Also wounded was his comrade in arms, Willy Cuba. The two of them alone, isolated and bleeding attempted to evade the troops by climbing what locals describe as a “chimney” a tight, nearly straight ravine.

At the top in quiet gasps, they found themselves stunned, facing Prado and his men. There was a brief exchange of fire.

According to Prado’s book “The Bolivian Diary,” the unrecognizable Che identified himself by saying “Don’t shoot! I am Che Guevara and worth more to you alive than dead.”

Prado’s decision to take Guevara alive, rather than kill him on the spot had significant reverberations. The first Bolivian version of Che’s death to the world was that he was killed in battle.

But the truth was more complicated.

After the battle, Prado walked the wounded-at-the-knee Che along the mule that carried the worse-wounded Willy Cuba to the hamlet of La Higuera where Prado turned him over to his superiors and Che was held for a day in a one-room schoolhouse.

There, Che smoked a cigarette offered to him by Prado, was interrogated, had a meal of a traditional Bolivian peanut soup, and was executed on October 9 under orders of La Paz.

The events marked the end of Che’s attempt to spread the communist revolution to Bolivia and the rest of South America. Of course, the real story is far more complicated than that. But the capture and execution and the way they happened solidified Che’s status as a martyr and revolutionary icon for leftists around the world.

Some twenty-thousand days later, in a vastly different world, General Gary Prado died of renal failure from complications of pneumonia which developed on top of a recurrent infection that had him hospitalised since April. Prado was wheelchairbound since 1981 when a misfire from one of his men hit his spine.

Born in Rome, Italy to Bolivian diplomat parents, Prado grew up in the Santa Cruz region of Bolivia. A cousin of then-Bolivian President General Rene Barrientos, Prado moved through the military ranks from Captain to Colonel at the time of the Guevara-led guerilla incursion in Bolivia.

After his defining role in the guerilla war, he rose to the rank of General and became a university professor and a diplomat. He served as Bolivian ambassador to Great Britain and Mexico as well as Planning and Coordination Minister for President David Padilla and advisor to President Jaime Paz Zamora.

His death was announced on social media.

“The Lord has just called my father, General Div SP Gary Augusto Prado Salmón, to His Kingdom. He died surrounded by his wife and children. He leaves us a legacy of love, honesty, and strength. He was an extraordinary person,” wrote his son Gary Prado Araúz in a Facebook post.

“For him the capture of Che was the most important thing he did in his life,” said his son in declarations to EFE after his death, stressing that his father “experienced imprisonment, exile, and clandestinity while fighting for his democratic principles.”

During the government of Evo Morales, General Prado served 11 months of home detention on charges of terrorism for which he was later cleared.

Max Prado, a first-cousin to the general recalled him as “very straight, a correct man who was a source of huge pride for him and for Bolivia,” stressing in comments to THE WEEK that he did his job as a military man, he did it well and honourably.

“He captured Che and handed him to the CIA. That they killed him was not his decision. He turned him over alive.”

In his writings, General Prado was critical of the Bolivian government’s handling of the aftermath of the capture of Che. He often spoke publicly against what he saw as corruption and incompetence in the military and political leadership. In later years he was known for his outspokenness on a variety of issues and was aligned with right-wing politics but was always known as the man who captured Che.

As perhaps a prominent figure in the communist revolutionary movements of Latin America during the 1960s, Che advocated for the use of guerrilla warfare to jumpstart “focos,” focal points of revolution, that he strategised would turn the entire continent communist as they had in the Cuban revolution.

The defeat of his guerrilla effort that began with Prado’s capture was a significant turning point in the1960s intense ideological and political tug-of-war between the United States and the Soviet Union, Che’s differences with Moscow notwithstanding.

The 1967 event defined Prado’s life but it also marked the end of Che Guevara’s revolutionary life. And that had significant implications for the broader Cold War context in Latin America.